The closing quarter of last year confirmed expectations for an ongoing solid expansion of the US economy, albeit at a slightly lower pace than in the previous quarters, and a slowdown of growth in the Eurozone due to the comparison with the Olympic Games period. On the other hand, growth accelerated in China, thanks to government stimulus.

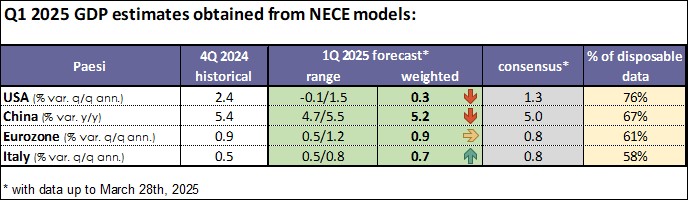

For the opening quarter of 2025, GDP forecasts yielded by the NECE Nowcasting models point to a significant weakening of the US economy due to the impact of Trump’ policies, while growth is seen to essentially stabilise in the Eurozone and China at the previous quarter’s levels, more moderate in the Eurozone and more solid in China, where it is still benefiting from government stimulus measures.

More in detail:

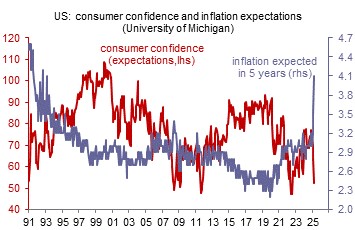

• In the US, NECE models point to a marked weakening of growth, forecast to stop at a modest 0.3% q/q annualised, from 2.4% in 4Q 2024. The strongest drag on growth is foreign trade, influenced by the impact of Trump’s policies, which has fuelled significant import growth due to front-loading ahead of the introduction of tariffs. This combined with a marked slowdown of consumption, due in part to rising inflation and in part to a physiological correction after the sharp increase recorded in the second half of last year. The slowdown may also be explained in part by consumer concerns over the effects of Trump’s trade policies, as indicated by the recent, sharp deterioration of consumer confidence

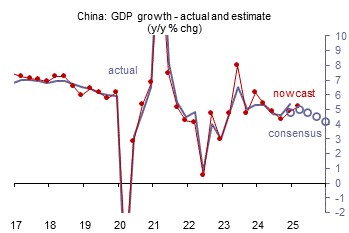

• in China the NECE models indicate that the economy is keeping up a solid pace of growth, of around 5% (only slightly slower than the 5.4% rate achieved in 4Q), still driven by the impact of the stimulus measures put in place by the government last autumn

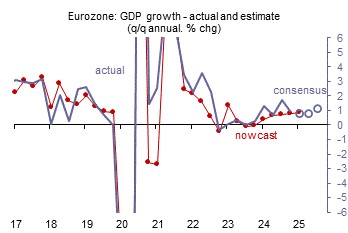

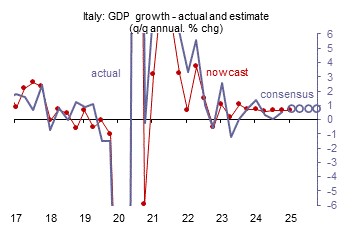

• In the Eurozone NECE estimates point to consolidating growth at moderate rates, similar to those seen in the closing quarter of last year, i.e. of around 0.2% q/q (0.9% annualised), resulting from a recovery of activity in the industrial sector (helped by a frontloading of orders in view of the introduction of US trade tariffs) and by a slight slowdown in services. Similar indications apply to Italy, for which the models point to a growth trend in line with the Eurozone’s, of close to 0.2% q/q

It should be said that the estimates have been drawn up based on incomplete data, i.e. 75% of economic data for the US, 67% for China, and around 60% for the Eurozone and Italy. As a result, the forecasts may undergo changes in the next few weeks.

N.B. The tables show the range of forecasts obtained from different econometric models that use real activity or confidence data, or a combination of both, alongside their weighted average (weightings inversely proportional to the forecasting error of the models). Data are indicated as annualised quarterly percentage changes, in order to guarantee comparability among countries. The sole exception is China, for which GDP data and the relative estimates are expressed as y/y percentage changes. The arrows indicate whether an acceleration or deceleration is forecast compared to the previous quarter.

Going forward, downside risks to growth are on the rise due to Trump’s trade tariff policies

Extending the forecast horizon to the next few quarters, risks to growth are tilted to the downside.

Trump’s policies are the main culprit, with particular respect to trade tariffs, although the cuts to state offices and staff implemented by the DOGE led by Musk are also playing a role.

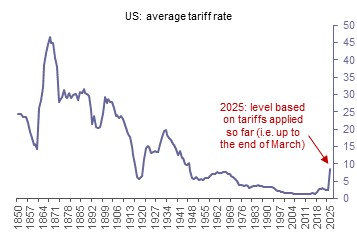

Even before is inauguration, Trump had announced his intention to impose new tariffs on imports, confirmed as soon has he took office: after twice hiking tariffs on Chinese imports by 10%, he introduced 25% tariffs on steel and aluminium import from all countries, and a 25% tariff targeting Canada and Mexico (later largely postponed to the beginning of April). Furthermore, the president announced that as of 3 April, 25% tariffs will be applied to all auto and component imports from all countries, on top of the “mutual tariffs” that Trump intends to announce on 2 April, and that target all the countries towards which the United States show a trade deficit.

In any case, Trump’s approach to trade tariffs, that have been first threatened, then announced, and lastly frozen in part or postponed, is ambiguous and confusing, and has resulted in mounting uncertainty, that has surged to long-term highs, beating by far the levels recorded before Trump’s presidency.

This uncertainty, if protracted, risks affecting the spending decisions of consumers and businesses, on top of the direct impact of the tariffs.

Effects are already materialising in the United States, where since the beginning of the year consumer expectations have worsened significantly, reflecting concerns over the inflationary impact of trade tariffs, while businesses are also confused by the approach taken by Trump, who was expected to craft more favourable policies in terms of both tax cuts and deregulation, of which there has been no mention so far, while the increase in trade tariffs risks forcing them to face higher production costs and lower profits.

In China and the Eurozone, business confidence proved resilient in the opening months of the year, as production and orders were font-loaded in view of the introduction of US trade tariffs. Also of help were government stimulus measures in China and the announcement of defence spending hikes in Europe and in Germany in particular, where Parliament approved a massive spending plan on defence and infrastructure, that required an amendment of the debt-containment rule (“Schuldenbremse”). However, it will take time for the financial package announced in Germany to translate into effective spending under the new government (yet to take office), whereas in China, the economy’s chances of keeping up its present pace of growth despite the substantial US trade tariffs will depend on whether or not the government puts in place further stimulus measures.

In the near term, risks to growth in the major economies are therefore skewed to the downside, all the more so at a time when the major central banks’ willingness to act in support of growth could be weakened by the inflationary risks tied to the trade tariffs (this is especially true for the Federal Reserve).

APPENDIX ON METHODOLOGY

NECE (Now Economic Cast by Eurizon) estimates are obtained using the Nowcasting econometric estimation technique.

This technique allows the forecasting, virtually in real time, of GDP growth, a reading which is released on a quarterly basis and typically at a lag of around one month after the end of the quarter considered. The forecasts are drawn up based on the information provided by high-frequency economic data (typically released on a monthly basis), made available during the quarter to which forecasts are referred, and therefore ahead of the GDP reading. This explains the use of the word “now”, to indicate the present situation, i.e. the GDP dynamic in the quarter under way, or in any case in the quarter to which the monthly data being released are referred. “Forecasting”, on the other hand usually refers to longer-term estimates.

The forecasts drawn up using the Nowcasting technique change as new relevant information is made available, and become progressively more accurate as data for the quarter considered are released, although they are still “forecasts”, and as such prone to error. The information may consist of both qualitative data, i.e. business and consumer confidence indices (soft data), or real activity data (hard data), such as industrial output, consumption, trade balance data, orders, etc. Lastly, some models (“mixed models”) are built using both types of data.